How the Institute for Replication is Making Social Science More Robust and Reliable

By Jeremy Klemin

Editor’s note: This article was published under our former name, Open Philanthropy.

Earlier this year, Open Philanthropy launched our $120 million Abundance & Growth Fund, a joint initiative between Good Ventures, Patrick Collison, and other private funders. Much of the Fund’s work is focused on accelerating scientific and technological research, which has been the central driver of the world’s remarkable economic growth over the last few centuries. One aspect of that work is support for metascience: the study of how to improve the way scientific research is conducted.

Even prior to the launch of the Fund, we were supporting metascience work from grantees like the Institute for Replication (I4R), which was founded in 2021 by Abel Brodeur to address a major problem in economics: many papers in top journals don’t hold up under scrutiny.

Because highly cited papers are often used as the evidence base for public and private funding decisions, we think that replicating studies to test their results can be quite impactful. But commercial actors lack the incentives to ensure that academic research is reliable — which means philanthropy is uniquely positioned to help create better conditions for scientific and technological development. As I4R continues to expand beyond economics, we wanted to highlight their work.

*****

If you ask Abel Brodeur about his interest in p-hacking — manipulating data or analysis to get a statistically significant result — he’ll be honest with you. As a master’s student in Paris 15 years ago, the young Canadian dabbled in that particular dark art while researching how public smoking bans affected smoking prevalence in the U.S. “I kept torturing the data until I could show a decrease of three or four percentage points,” says Brodeur, who is now Chair of the Institute for Replication (I4R). “I ran 1,000 regressions, and 950 of them showed that nothing was going on. The more I thought about what I was doing, the more I realized how stupid it was.”

To his credit, Brodeur eventually submitted a master’s thesis showing no significant effect, even though he assumed academic journals wouldn’t publish it. (He was correct.) Yet when he looked at highly cited papers on the topic, many reported dramatic effects — often using the same data! Brodeur had stumbled upon what would soon become a contentious issue in economics: a lot of economic research does not replicate.

The broad term “replication” actually covers several ways of checking the reliability of research. It can entail redoing an entire experiment to gather your own data, or less time-intensive checks, such as reanalyzing the original data using the author’s code. The latter is often referred to as “reproduction,” although there is no broad consensus on these terms. Papers can fail to replicate for many reasons — from outright fraud and p-hacking to simple coding mistakes. Whatever the cause, the stakes are high. If a research finding doesn’t consistently appear even under ideal test conditions, it very well may not apply to real-world conditions.

While replication problems are not unique to the social sciences, the field is particularly vulnerable. Jordan Dworkin, a senior program associate for Open Philanthropy’s Abundance & Growth Fund, explains that because fields like economics depend heavily on the analysis of observational or quasi-experimental data, there are ample opportunities for researcher discretion. “Even if a researcher is acting in good faith, these opportunities can lead to ambiguity and difficulty replicating,” he says.

After enrolling in an economics Ph.D. in 2011, Brodeur became involved in a growing movement of economists who sought to understand how widespread the problem was. He had good timing: “replication crisis” was coined that same year to refer to a parallel problem in psychology, and the Center for Open Science, a leading replication advocate, launched in 2013. Brodeur continued to research the problem, and in late 2021, he founded the Institute for Replication: a nonprofit aimed at replicating studies published in top economics journals.

“Institute” was mostly aspirational at first, as I4R struggled to secure funding. “Whenever we applied to traditional funders, we’d get a zero on the ‘novelty’ assessment, which would kill our proposal,” says Brodeur. Viewing replication as devoid of novelty misses I4R’s whole theory of change.

In 2022, Otis Reid, then the head of Open Phil’s Global Health & Wellbeing Cause Prioritization (GHWCP) team, was considering whether to recommend a handful of grants to support work in immigration policy and telecommunications in low- and middle-income countries. He wanted to confirm that the supporting research was robust before moving forward, so he hired I4R. “We can’t do due diligence on the millions of studies published every year,” says David Roodman, a Senior Advisor on Open Phil’s GHWCP team. “But the ones that implicate the greatest stakes in human lives or dollars for decision-makers? Those deserve extra scrutiny.” In its early days, I4R would compensate researchers with $5,000 per study to check for coding errors, assess how robust results were to alternative modeling assumptions, and see if results held up in other data (when available). When a single paper can inspire millions of dollars in grants (or follow-up research), it’s a small price to pay.

Roughly six months after I4R’s work for Reid, Matt Clancy, who at the time led our work on innovation policy, requested a call with Brodeur to discuss the possibility of a grant from Open Phil. Brodeur describes their first meeting as almost awkward: he had prepared a long spiel justifying his work, but Clancy interrupted him a few seconds in. “I was like, ‘Of course we need replications!’” says Clancy, recalling the exchange.

Replication Games: A new playbook for reliable research

Aside from its work on individual papers, I4R also runs a few “Replication Games” each month. The games bring together academics to replicate papers from leading journals in economics and other disciplines. Recent topics include the effects of exercise on human cognition and the trustworthiness of GDP growth estimates from non-democratic countries.

In a Replication Game, organizers assign a small group of researchers a paper to replicate, based on the group’s expertise. Teams then attempt to duplicate the study’s results with the same data but different methodological assumptions.

These games support I4R’s goals in two key ways:

Catching errors before they shape policy

Replication Games facilitate the replication of highly cited studies that have a good chance of impacting the allocation of public and private funds. In-person collaboration speeds up the work, and organizers are able to keep costs down by taking care of operations and logistics for the researchers. The Games also help early-career economists develop important skills, such as how to use replication tools for tasks like testing alternative specifications or running meta-analyses.

Changing the incentives for researchers

This widespread effort feeds into I4R’s second theory of change: shifting the norms of academic research. Dworkin, who recommended our most recent grant to I4R, explains: “If my data and code are going to stay private, I can run 10 versions of an analysis and then publish the most favorable result. But if there’s a 50% chance that I4R is going to reproduce my paper and check whether its findings are robust to other approaches, then my incentive to hide the ball is dramatically reduced.” Brodeur hopes that replicating papers helps to dissuade future researchers from pulling the same tricks he considered as a master’s student.

Publication bias: the perfect villain

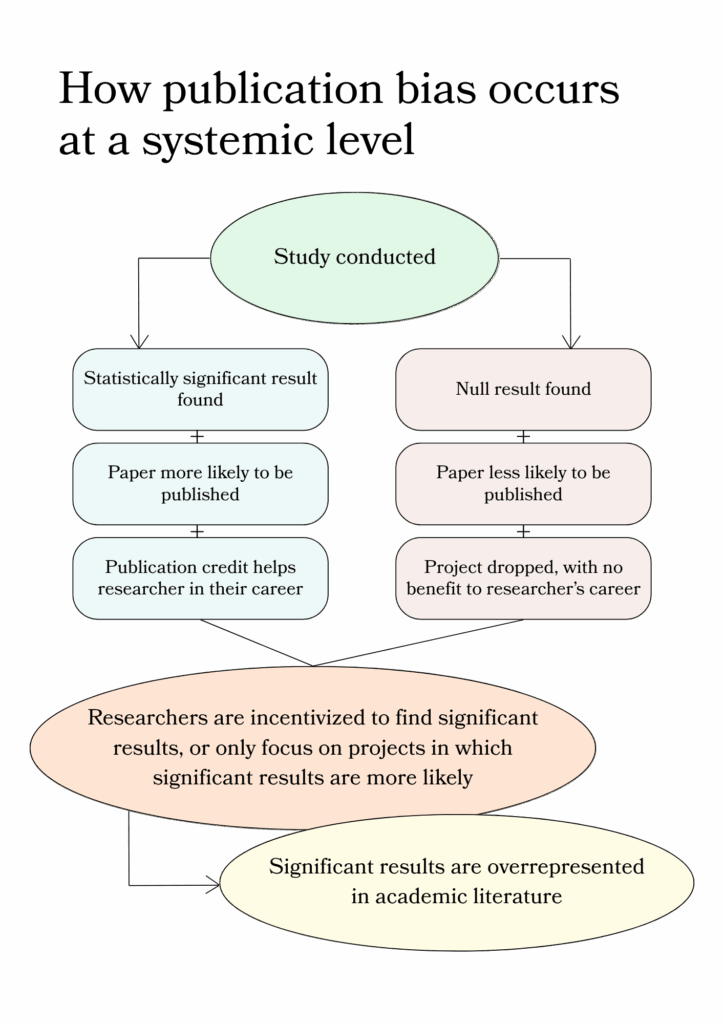

While outright fraud does occasionally happen, the larger problem is a system that incentivizes academics to submit positive, exciting results for publication. “It’s more likely that a paper showing a huge effect is going to get published than a paper showing null or small effects,” says Dworkin. Researchers know this, and because tenure depends on bylines in leading journals, they often feel pressure to find significant effects. The journals, in turn, are incentivized to publish work that is more likely to get cited because it increases their own prestige. These dynamics systematically distort the literature, making it difficult for decision-makers to distinguish between genuinely effective approaches and those that appear successful only because negative results remain hidden.

Roodman sees this process, often called publication bias, as almost unconscious: “If I tell you as a hunter-gatherer descendant where the blueberries are, that’s more exciting and more important than if I tell you where they’re not.”

In Brodeur’s view, the biggest barrier to shifting these incentive structures is that many economics journals either do not require or do not enforce data and code sharing. Making this information public by default would make data manipulation and cherry-picking much harder to get away with, and push economists to ensure that their work can withstand scrutiny.

I4R works with journals in several contexts: ongoing formal partnerships, publishing metastudies produced at Replication Games, and collaborating on replication-themed issues. Recently, I4R replicated 17 papers across two editions of the prestigious American Economic Review, and found that many of the results were not robust. Convincing journals to participate in these initiatives can be challenging, as editors have few incentives to participate in a replication that may discredit a study they published.

Even if a given replication reflects well on the journal, it means more work. And the issue rarely “resolves” after a single replication; someone must also mediate disputes between authors and replicators. “To some extent, I blame the editors of top journals for not publishing enough replications,” says Brodeur. “But I also sympathize with them. Mediating is incredibly complicated.” Brodeur and other I4R staff often serve as mediators themselves. While they can’t convince every journal editor to make replications a higher priority, they can help to ease the burden of mediation for those who are inclined to make a genuine effort.

*****

When potentially impactful work lacks a commercial incentive, Open Phil is excited to step in — as we did with our recent grant to support I4R’s expansion into air pollution and deforestation. But our role is limited; it is Brodeur and his peers who will double-check the data and mediate the monthslong disputes.

Brodeur’s ultimate goal — to change the incentive structures that govern academic publishing — will create friction among economists, and he knows it. But he has always been more interested in bringing the community together than fracturing it. “Going over somebody else’s code with a team of other researchers changes how you think about your own research,” says Brodeur. “We’re a community trying to fix its own mess.”